Today, in August 2019, I am older than three of my four grandparents were in summer 1969. My oldest grandfather, Leonard Harbison, was only a year and a half older than I am now.

Back then, of course, they all seemed ancient to me. I keep that in mind as a college professor, surrounded daily by 20-year-olds.

The summer of ’69 is being talked about throughout this, the 50th anniversary. It seems that each week is the golden anniversary of some significant, grand, or unsettling milestone. The Who’s brilliant and pretentious “rock opera” Tommy was released in May 1969 and formed a significant part of the soundtrack of that summer. So did Jimmy Webb’s “Galveston,” recorded by Glen Campbell – which most of us didn’t realize was an anti-war song. The counter-culture biker movie Easy Rider was in theatres, as were John Wayne in True Grit and the X-rated Midnight Cowboy.

The Stonewall uprising occurred in June, signaling the birth of an organized gay rights movement. And Chappaquiddick, an event that forever stained Sen. Ted Kennedy’s reputation, occurred in July. But the first manned moon landing was the most significant event of July, and of the year.

Since I currently live in Huntsville, there has been a certain level of Huntsville-style hoopla in celebration of the first manned moon landing in July 1969. The Saturn V rocket that propelled the Apollo missions was created in Huntsville and there is justifiable pride in the accomplishments of NASA that pervade the community all the time, regardless of the year. What Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant is to Tuscaloosa, the Saturn V is to Huntsville.

Back then, my interest in the myth of the “final frontier” was peripheral at best. It was exciting to watch launches from Cape Kennedy on classroom televisions in the 1960s, and it was exciting to watch the capsules’ safe splash-downs in the Atlantic afterwards. The whole country grieved when the three Apollo 1 astronauts were killed in a fire during a pre-flight launch pad test in 1967.

Two and a half years later, my family was living in Nashville when Neil Armstrong made that first “small step” on the moon in that grainy video transmitted back to Earth. My memory of that moment is vivid still. I remember that when the satellite transmission ended on broadcast television, I walked out into our front yard and looked up at the moon. The fact that two Americans were sitting there, and that another was orbiting to facilitate their return, is still daunting, inspiring, transformational to think about.

August of 1969 is particularly memorable for two tragedies – Hurricane Camille, which devastated the Mississippi Gulf Coast, and the Tate – La Bianca murders perpetrated by the “Manson family” in the hills of Los Angeles. Some say that the gruesome Tate – La Bianca slayings signaled the end of the 1960s, while others make the case that Nixon’s defeat of McGovern in 1972 was the end of the ’60s era. Either way, the Tate – La Bianca case signaled an end to a certain optimistic innocence that characterized large chunks of that decade, despite the war protests and social and political upheaval that fomented throughout those years. August 1969, of course, is also remembered for a slipshod celebration that became an enduring legend – the Woodstock music festival, held on Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in upstate New York.

My first memory of Hurricane Camille is a strange one. My family was traveling from Six Flags in Atlanta to Birmingham and made a rest stop in Anniston late in the night. While we were waiting for Mother, Dad struck up a conversation in the parking lot with another man traveling with his family; they began to talk about the massive hurricane that was then bearing down on the Mississippi coast. Somehow, that conversation conjures a memory of the animated neon Goal Post Bar-B-Q sign, an iconic Anniston fixture depicting a football player kicking a football through a goal post. Our rest stop was down the highway from the barbecue joint and I was watching that sign as the two grown-ups chatted, we waited for my mother, and my brother slept in the back seat.

These distant memories are stimulated by a recent viewing of fanboy Quentin Tarantino’s latest ultra-violent fantasy, Once upon a Time … in Hollywood, set in the summer of 1969. The film focuses on two fictional characters, a fading western star, Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), and his stunt man, best friend, and jack-of-all-trades, Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt). A presence throughout the film is the very non-fictional Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie), who, with her husband, director Roman Polanski, rents the house next door to Dalton. Tate, who is 8½ months pregnant at the movie’s end, floats through the proceedings with a serenity and presence that are exhilarating to watch. Another recurring presence throughout the movie is members of Charles Manson’s hippie cult, skulking regularly on the edges.

Tarantino weaves a shaggy dog story with many loose ends and an entertaining jumble of real-life and fictional characters. The movie begins on February 9, 1969 (my 14th birthday), sets up the characters, and jumps, later, to August 9 of the same year. Tarantino assumes that the audience knows its 1969 pop culture history and throws teases and period references in with the imaginative fictionalization. Quick appearances are made by actors playing Steve McQueen, James Stacy, Sam Wanamaker, and other real-life personalities of the era. We briefly catch a bit of a car radio news broadcast announcing the sentencing of Sirhan Sirhan, who assassinated Robert Kennedy in 1968.

In a lovely, carefree interlude, the camera follows Cass Elliott, Michelle Phillips, and Sharon Tate as they hold hands, running through a party at the Playboy mansion, and begin to dance. In another scene, three Manson girls are seen holding hands, smiling like Moonies, singing and skipping down an L.A. sidewalk.

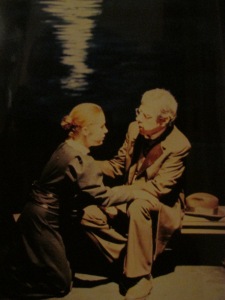

It’s a fascinating and enjoyable movie, made moreso by its frequent dips into a splashy late-60s reality, but always tempered by the very real presence of the darkness that lurks at the Spahn Ranch, the former western movie lot that has been infested by Manson’s followers and hangers-on. In a tense scene, Cliff goes to the Spahn Ranch – a place he knows from past film and television shoots – with a hitchhiker he’s picked up in Hollywood. When he insists on seeing George Spahn, an old friend who is now the blind and aging owner of the ranch, the mood shifts. We worry for the safety of Cliff, and for the foreboding scenarios still to emerge.

I have never warmed up to DiCaprio as an adult actor, but his portrayal of a washed-out, whiny former tv star is effectively irksome and desperate. Brad Pitt, who is aging gracefully, has rarely been as appealingly authentic as he is in his role as Cliff – who might have murdered his wife, but moves through the world with a carefree and amused attitude.

Sharon Tate, who was only 26 when she was murdered, is most remembered now for the last day of her life. In Tarantino’s movie, there is a celebration – through Robbie’s performance – of Tate’s joie de vivre and potential. We follow her as she goes through her day, and discover a complex, upbeat woman far removed from the tragic headlines that have become her legacy. Tarantino’s camera worships Pitt and Robbie in this film, and doesn’t hesitate to linger and marvel at each of them when it has the opportunity.

Obviously, since this is a Tarantino film, there is violence; sometimes, that violence seems gratuitous. Here’s my stance on Tarantino and violence, and I realize there will be those who disagree: To me, Tarantino’s violence is so over-the-top and wild that I find it hard to take seriously. One stifles the urge to laugh at the outrageous excess; the filmmaker does not glorify or even endorse violence, it seems to me, but uses it as a device to celebrate the absurdity all around us to which he seems so drawn.

The Russian playwright Anton Chekhov referred to his plays as “comedy” and many find that hard to wrap their mind around. I think I get it with Chekhov. He explores and revels in the absurdity of our surroundings and everyday lives. I don’t think of Tarantino as “Chekhovian” by any stretch, but I think his prankish and warped world-view enjoys taking his audience to the extremes of a violent society.

For those who think they know how Once upon a Time in Hollywood must inevitably end, and are avoiding it for that reason, I suggest that you see for yourself. Without going into detail, I think the final image of this movie is one of the sweetest images I’ve seen in a movie in years. It’s a moment that portends a whole new trajectory for the end of the ‘60s – an ending that was earned, but, sadly, was never achieved.