St. Vincent’s Chapel

Points of view and frames of reference have been changed by the times in which we exist. My mother was recently discharged from the hospital to a rehab facility. Her transport was late arriving and we had fallen asleep in the hospital room. Around 11:00 p.m., the lights flashed on abruptly and woke us up. Two burly paramedics came quickly into the room, followed by a frantic nurse saying, “They’re here.” There was a mad rush, gathering bags, the exchange of paperwork, transfer from hospital bed to stretcher – we were swept out of the room in less than five minutes.

The next day, describing the experience to a friend, I heard myself say, “It felt like an ICE raid.” That is a comparison that wouldn’t have come to mind a year ago. But this is the state of America in 2026. (In December, I had to go to three post office branches to find stamps. We’re not talking special stamps or holiday stamps – just regular postage stamps. “Great” indeed.)

December and January have been fraught with emergency rooms, ICUs, hospital rooms, rehabs, and home health care. Because of a prescription mixup, the cycle had to be repeated. This past holiday season has felt at times like the annual “Airing of Grievances” at Festivus.

It is not my intent to air grievances but to acknowledge those moments of grace encountered in trying times. It seems that with hardship, pain, and stress, the moments of grace become more heightened and profound – more deeply felt. I was raised in an evangelical church but my spirituality evolved in a much more private and personal way. In challenging times, moments of spontaneous kindness take on an added texture and are an assurance that there is still good and caring in a troubled and troubling world where cruelty, monsters, and crazed madmen seem to be taking control. Even a few moments watching the backyard bird feeders can be an effective balm in troubled times. Letting one’s mind rest becomes key.

The phrase “thoughts and prayers” is as hollow as the politicians who say it on auto-drive whenever an event occurs that they have no plan to substantively address (sorry, there’s a grievance there). But it means something when a true expression of concern comes from a person who genuinely seems to care. When I departed a parking deck after several sleepless nights of sitting at a hospital bedside recently, the attendant took my payment and then leaned in, placing a hand on my shoulder. She said, “Everything will be alright, sir. Now go try to get some rest.” She knew without knowing and there was a moment of relief and transcendence as I pulled onto the busy street.

I rescheduled a doctor’s appointment recently due to caregiving responsibilities. In talking to the scheduler, I mentioned in passing that my mom was in ICU. As I went on, the scheduler said, “Wait! Tell me her name.” I told her Mother’s name and she said, “As soon as we hang up, I’ll pray for her.” I know she did.

Over the weekend, the woman who replaced me in my old faculty position sent a video. It was my former student who was a recent finalist on “The Voice.” My faculty colleague met her at a reception and asked if she’d like to say hello to me. The message was sweet and loving and began with “Hello, Mr. Journey, it’s Jazmine … I wonder if you even remember me …” Of course I remembered her and had followed her success on “The Voice.” I had wondered if she even remembered me. The message came – again I was sitting beside a bed in a rehab center – at a low point. It gave me a boost of energy and distraction to move forward. Hearing from successful former students is a reminder that my teaching years were worth something.

Afterward, I learned that the colleague who sent the video and her sister were in the process of caregiving for their own mother in the hospital. You never know what burdens the person you pass on the street or in the store might be dealing with. You never know what’s going on behind the scenes – what prompted that tart retort or insensitive comment, that teary response.

Mother’s most recent hospital stay was at St. Vincent’s, arguably Birmingham’s oldest hospital, founded by the Sisters of Charity in 1898. It has served my great-grandmother, my grandmother, and my mother since the days when the Sisters wandered the halls in full habit. St. Vincent’s was a private Catholic hospital until the church decided to divest itself of its healthcare interests. UAB, Birmingham’s branch of the University of Alabama System, with its medical center, saw the opportunity to once again feed its Trumpian zeal to swallow Birmingham’s Southside whole (grievance) and heeded the call. The good news is that St. Vincent’s is still with us; the bad news is that decline in healthcare seems to occur whenever UAB takes over a well-established medical facility.

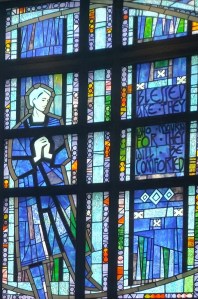

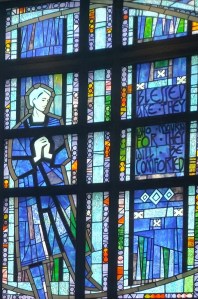

With the takeover, UAB began to clear out the Catholic iconography of the facility, throw the UAB logo on everything, and treat the fragments that were left as historic relics. Fortunately, the hospital’s serene Chapel has been kept, sans the crucifix that once hung above the altar as well as other Catholic-specific artifacts.

St. Vincent’s Chapel

The Chapel at St. Vincent’s was across the main hospital from my mother’s room, but I sought it out on a recent Saturday morning. The stained glass windows, inspired by the Beatitudes, remain. The room is a spot for meditative grace and quiet reflection. A few stolen moments can “restoreth my soul” in the midst of the intense strain of a busy hospital environment.

Inspiration was never my strongest trait as a writer or a speaker; a natural skepticism comes through no matter how serious my intent. But I’ve learned to seek out moments of inspiration and cherish them. It might be a moment of solitude or a piece of restorative music. Since Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead passed, I find myself listening to “Cassidy,” my favorite song by the Dead, regularly. That brings back warm memories of times past.

The graceful moment might be a friendly remark in a grocery checkout line or a private chat with a hospital nurse. Recently, I heard from relatives I haven’t heard from in a while. A cousin called with sobering news and, in the midst of a thoughtful conversation, we started laughing at a memory of an afternoon spent as ten-year-olds “helping” our grandmother paint a bathroom. These stolen moments are all around if we just look for them. More importantly, we need to recognize and cherish them as they happen.

St. Vincent’s Chapel