One of my favorite opening lines in all of dramatic literature comes from Masha in Chekhov’s The Seagull. At the beginning of that play, Medvedenko asks Masha why she always wears black. “I am in mourning for my life,” she says. I was thrilled recently when I stopped by a neighborhood shop on my way home from work. I was wearing a black shirt and black trousers and the shopowner, a friend, asked me why I was dressed all in black. It was the perfect opening for a literary quote and I grabbed it.

One of my favorite opening lines in all of dramatic literature comes from Masha in Chekhov’s The Seagull. At the beginning of that play, Medvedenko asks Masha why she always wears black. “I am in mourning for my life,” she says. I was thrilled recently when I stopped by a neighborhood shop on my way home from work. I was wearing a black shirt and black trousers and the shopowner, a friend, asked me why I was dressed all in black. It was the perfect opening for a literary quote and I grabbed it.

I am a man with strong opinions on many things and many of those opinions were formed relatively early in life. I was fortunate to have a high school English teacher who was not intimidated by the Russian master Anton Chekhov and I remember loving Chekhov’s The Three Sisters the first time I studied it in a high school lit class. It was then that I decided that Chekhov was my favorite playwright and he is still my favorite playwright to this day. I must admit that Sam Shepard is a close second. And I will direct a Chekhov or Shepard play at any opportunity.

Chekhov referred to his plays as “comedy.” That fact still baffles many people familiar with the work. It never baffled me. As a Southerner, I have always felt a kinship with the playwright’s sly and droll sense of humor.

Chekhov’s plays examine the idiosyncrasies and foibles of the human condition and he seems on occasion to wince patiently and lovingly. This is what we mortals are, Chekhov seems to assert, as ludicrous as we may be. Chekhov was trained as a physician and examines his characters fairly and humanely but with clinical detachment.

Chekhov’s down-to-earth sense of humor reminds me of my favorite quote from William James: “Common sense and a sense of humor are the same thing, moving at different speeds. A sense of humor is just common sense, dancing.”

I once congratulated a friend on her performance in Chekhov’s final play, The Cherry Orchard. “Oh please,” she snapped. “I hated that performance and I hate that play. He’s so damn depressing!” I realized that her cluelessness about the play and the character may have been what contributed to her excellent and amusing performance as a headstrong woman who couldn’t see the forest for the (cherry) trees.

I have had the opportunity to direct Chekhov plays a couple of times, to act in a couple, and to see many productions over the years. When I directed The Seagull, I played up the abundant humor of the piece. Audience members thanked me for it afterward. An actor friend who drove a hundred miles to see the production grabbed me at intermission and said, “Thank God. Finally a performance of The Seagull where an audience is actually laughing at the funny parts!” (one of my favorite reviews ever).

As the various characters struggle through their various issues – loveless marriages, aging and decay, lack of talent, greed and ruthless ambition, fickle lovers, loss – they often make bad choices and those bad choices are often accompanied by overwrought and over the top overreactions. We smile to ourselves and I think we recognize ourselves in much of what transpires on stage.

I have dealt with The Seagull in many stages in life. When I was a college student, I thought it was the perfect play for college students as it examined our need to define ourselves, set our goals, and perhaps overreach beyond our capabilities. Now that I’m older, the play speaks directly to me on a profoundly different level but with the same intensity. And much of the journey of the play is still very touching and funny.

Konstantin, one of the major characters, does commit suicide in the end. Oh well, there’s that…

Chekhov’s characters are often in turmoil and despair. He does not make fun of them, but he does handle them gingerly and allows an attentive audience to smile at their overwrought reactions to situations that might often be easily remedied with a little common sense and effort. Often it seems his characters are frozen in inaction and ennui simply because they can’t stop talking about their despair. One thinks Just go to Moscow and stop whining about it after listening to the title siblings of The Three Sisters long for Moscow for four acts. To me, that’s funny.

Anton Chekhov died in 1904 at the age of 44. He died of tuberculosis but almost until the end he was writing letters assuring his correspondents that he was well on the road to recovery. Chekhov was a doctor; he knew better. At the end, a doctor who was attending Chekhov ordered a bottle of fine champagne with three glasses. He poured full glasses of champagne for Chekhov, Olga – Chekhov’s wife, and himself. According to Olga, Chekhov finished his glass, smiled, and said, “It’s a long time since I drank champagne.” Then he rolled over in his bed and quietly died.

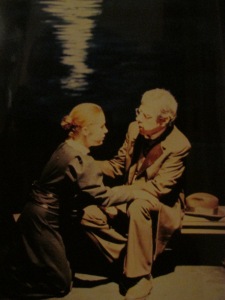

(The image is Mandy Erbes and Joseph C. Wilson as Masha and Dorn in The Seagull, directed by Edward Journey, at Longwood College in Farmville, Virginia, in September 1993.)