“What makes Iago evil? Some people ask. I never ask.”

Those are the opening words of Joan Didion’s 1970 novel Play Is as It Lays. I do not tend to memorize lines from books, but those three lines have rung in my memory ever since I first read that book and fell in fascination with the writer who created that detached, precise, and misleadingly cool voice. The famous photos of Didion with her Stingray and of Didion, drink and cigarette in hand, standing on her Malibu deck with her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne, and their daughter, Quintana, are iconic symbols of her place in the culture as a commentator for a distant and captivating California cool. She always seemed to harbor secrets.

Didion’s central California upbringing informed her prose, even as she spent most of her adult life in Manhattan, writing books, essays, and film scripts about all manner of topics. A decade ago, I presented a paper at a literary symposium proposing Didion as a California regionalist. In that presentation, I commented that since I first read Didion’s essay “In Bed,” in which she memorably chronicles how she deals with chronic migraines, a migraine always makes me think of California. It was a light-hearted comment, based in fact.

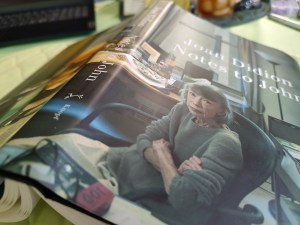

Didion died in 2021, but when I heard that a new book of her writing was being released this year, I immediately pre-ordered. Notes to John, a book of Didion’s detailed notes to her husband about her therapy sessions from 1999 to 2003, is controversial. One reviewer called it the “saddest and strangest book you will read this year.” Some people ask if the publication is ethical – would Didion want these notes to be public? Are these details about her family that she would choose to share? Are notes intended for her husband only in good enough shape to be published in book form? Who authorized the publication, and why? Who edited the notes? Who wrote the introduction and the afterword?

I never ask. But I read the book and, once I got started, I found it hard to stop. I did wonder, though, about some things. Since the notes were written for John, to keep him up on the trajectory of her therapy, I wonder if she edited what she wrote for his consumption. They were married for almost forty years; surely she had complaints about John to discuss with a therapist. Yet, in her detailed notes, she never quite criticizes her husband. When someone asked John about going into therapy himself, he groused, “I’m a Catholic, we have confession.” (After which the questioner asked how long it had been since he went to confession; this makes Joan’s Dr. MacKinnon laugh.) Much of Dr. MacKinnon’s commentary in the sessions is verbatim. One wonders if Didion’s memory was really that prodigious.

The tragic context for the notes, and for the therapy, is the problems Quintana is going through with alcoholism and a general lack of direction. Quintana’s therapist, Dr. Koss, suggested that Joan see a therapist, recommending Dr. MacKinnon. My biggest concerns about ethics come from the detail – throughout the notes – that Dr. Koss and MacKinnon are freely sharing details of their sessions with each other and discuss certain details about those sessions with Joan and Quintana. I must assume that Joan and Quintana gave permission for the sharing of information.

Didion’s essay on Georgia O’Keefe in The White Album (1979) gives a charming snapshot of the seven-year-old Quintana. Didion writes about seeing an O’Keefe exhibit in Chicago with her daughter. While they view O’Keefe’s cloud paintings, Quintana, mesmerized, asks her mother “Who drew this?” When she is told the painter’s name, she says, “I need to talk to her.” Quintana was a recurring presence in her mother’s writing and was a central presence in Didion’s two important twenty-first century works, The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights – books which dealt with Didion’s reaction to the death of her husband and, later, her daughter. Quintana’s struggles as an adult are full of hope and decline and serious alcohol abuse. These notes provide insights into her struggles and the collateral damage to her parents.

There is damage all around. In her sessions, Didion reflects on her own life – the legacy she leaves behind and the time she has left in her life. I realized that, at the time of these therapy sessions, Didion was close to my current age. She speaks of moving around during her growing up years and the feeling of frequently being the “new kid” in school. She speaks of taking jobs for the money – often her screenwriting assignments – and sacrificing time she would rather spend on activities and writing that she had a passion for. She speaks of her California family and of the values they instilled, and the values she rebelled against. In an intriguing California aside, Didion informs Dr. MacKinnon that the New York-style cocktail party is not a fixture in California; because of the distances involved in entertaining, she says, Californians entertain their guests at dinner instead, and everybody leaves around ten. Such details are sprinkled throughout a therapy that touches on issues of codependency, dysfunction in families, detachment, displacement, aging, and personality disorders.

As much as I admire Didion’s writing, I always wondered if I would like the writer. After reading Notes to John, I think I might; we have much more in common than I realized. I feel, as many might, that in eavesdropping on Didion’s intimate and extensive notes, I have garnered knowledge and insight into my own circumstances as a caregiver, sharing in the challenges of a life that was quite different from my own.

Notes to John is a heady book. It’s hard to know Didion’s intent, but it’s so well-written and true to the writer’s style that I suspect she foresaw that her notes might have a life beyond John’s eyes. The principals in this story have all passed on, and I hope they would appreciate their story and struggles bringing support to readers. I am grateful that this challenging chunk of their life was shared.